Buddy Guy’s long journey to the Hancher Auditorium stage this evening began in 1948 when the “wooden shack built up on pillars” in which he and his parents and brothers and sisters lived in Lettsworth, Louisiana, was electrified. Buddy was twelve then, and as he recalled decades later in When I Left Home — his 2012 autobiography written with David Ritz — the “little light bulb in our cabin didn’t improve life much,” but “the beat-up used phonograph that played 78 records, changed everything … I thank God that my daddy had this one record by John Lee Hooker called ‘Boogie Chillen.’ That’s the record that did it.”

Jazzy, jump blues recordings featuring suave vocalists backed by horn sections playing intricate arrangements dominated the R&B charts in 1949, but “Boogie Chillen’” topped them all with a starkly primeval sound. As Buddy describes Hooker’s hit, “Wasn’t anything more than one guy playing his electric guitar by himself. Notes were simple. Words were simple. Words didn’t even rhyme. But the groove got to me. The mood was so strong that after the song had done played, you had to play it over.”

Hooker’s relentlessly tapping foot and a one-chord boogie riff created a hypnotic musical bed as he sang about a boy desperate to boogie despite the fact that “my Mama, she didn't 'low me / Just to stay out all night long.” But one night, Hooker sang, the boy “heard mama 'n papa talkin’ / I heard papa tell mama / Let that boy boogie-woogie / ‘Cause it's in him, and it got to come out.” Hearing this lyric, the young Buddy Guy “figured that this John Lee Hooker had to be talking about me. I figured that one way or the other I had to get me a guitar…”

Buddy got his guitar one Christmas when his father purchased a two-string instrument, after some serious negotiation, from the local songster, Henry “Coot” Smith. Coot wanted five dollars for it. Buddy’s dad offered four. They settled on $4.35. Whether the instrument was a six-string guitar missing four strings or a homemade cigar box guitar or a homemade, two-string diddley bow, we aren’t told. My money is on the diddley bow. After the transaction had been completed and just before Coot fell deep into his wine, Buddy got a quick lesson in playing “Boogie Chillen,’” and “Life ain’t never been the same since.”

Until then, as Buddy tells his story, “My head was filled up with music I couldn’t play.” Now, with a guitar in his hands, the music in him was coming out. His brothers and sisters may have tired of his playing of Hooker’s repetitious song over and over again, but a stranger who walked by as Buddy was out on a porch “fooling with a new song by John Lee Hooker called ‘I’m in the Mood,’” was so impressed by what was coming out of Buddy that he offered to buy the teenager a real guitar. The stranger returned the next day to make good on his offer, spending $52 on a Harmony six-string for Buddy, who was overcome with gratitude: “All I could say was ‘thank you.’ I thanked the man who bought it, I thanked the owner of the store, and in my silent mind I thanked the Good Lord in heaven.” He wasn’t sure at first “what to do with them strings, but I was learning fast … Wasn’t long before I was playing ‘Boogie Chillen’ with all six strings. What a difference between two and six! Was like I had a whole orchestra in my hands.”

Buddy absorbed all the blues he could, listening to Lightnin’ Hopkins on the record player at home; to Smokey Hogg, Willie Mabon, J.B. Lenoir, and Howlin’ Wolf floating in from a station in “far-off Tennessee” when “the weather was clear”; and to Muddy Waters, Little Walter, and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup on the jukebox at the local general store. (Crudup’s song “That’s All Right” would soon send Elvis on his road to stardom.) When Lightnin’ Slim made a live appearance at that local store, Buddy focused his “eyes on [Slim’s] fingers like a hound dog focused on a rabbit hole” and learned about the power of blues to attract people. At show’s end, Slim said, “Didn’t I tell you, boy? Folk come buzzin’ in like bees to honey.”

Meanwhile, the young unknown guitarist worked as an LSU maintenance man by day and a service station attendant by night, and, as if two jobs weren’t enough, he ran a side hustle, selling discarded “pig’s head[s], chitlins, and feet,” unwanted by an LSU butchery course, to “the folks in the neighborhood who knew how to cook it.” Eventually Buddy was invited to play at a Baton Rouge barroom by yet another stranger coming out of nowhere to help when he happened to hear Buddy practicing during a lull in service station work. Unfortunately, once Buddy got onstage, “shyness got the best of me. So I turned my back on the crowd and sang to the wall.” He was fired.

Then, at the Baton Rouge Masonic Temple, he heard Guitar Slim, whose song “The Things That I Used to Do,” arranged by Ray Charles, reigned atop the 1953 Rhythm and Blues charts. From this Slim, Buddy learned a lesson about guitar slinging showmanship from a performer who wasn’t the least bit shy: “He was slick as grease and dressed to kill — flaming red suit, flaming red shoes, flaming red-dyed hair … He played his guitar between his legs, played it behind his back, played it on his back, played it jumping off the stage, played it hanging from the rafters.”

Soon Buddy was imagining a life in Chicago: “I didn’t think I was good enough to make a living picking the guitar up there, but I sure did dream of getting a glimpse of Muddy and Walter and them driving around in their fine cars.” It took him two years to accumulate a $600 stash, and on September 25, 1957 — armed with that money, his Les Paul Gibson, a demo recorded at a local radio station, and a letter of introduction to Mr. Leonard Chess (co-owner of Chess Records, the premier Chicago blues record label) — he boarded a northbound train.

The letter of introduction failed to open the recording magnate’s door. All that Buddy’s first visit to the Chess Studio accomplished was to make him feel as insignificant as a “bug in the rug,” as he watched a recording session of the Spaniels singing doo-wop: “I saw that [the session guitarist] Wayne Bennett was reading music set in front of him on a stand. He read it beautifully. I had to admire that because I couldn’t — and still can’t — read a note.” Bennett — now celebrated for decades of recording with Bobby “Blue” Bland — had admired Buddy’s guitar as the newcomer stood forlornly in the lobby, and the studio ace asked to borrow it for the session. Buddy’s guitar had made it onto a Chess recording, but not with Buddy playing it.

Five or six months later, he was broke, starving, and walking the streets of Chicago’s south side with his guitar — “thinking of borrowing a dime to call my daddy in Baton Rouge for a ticket home. I was ready to swallow my pride.” Fortunately, for blues lovers around the world, yet another stranger intervened. Noticing Buddy’s guitar, the man asked, “Can you play that thing?” When Buddy answered, “Yes, sir,” the man offered him a drink in return for some music. Impressed by Buddy’s rendition of Jimmy Reed material, the stranger brought Buddy home to show him off for his wife, and then the two took Buddy to the 708 Club where the fiery Otis Rush was playing. The man screamed at Rush that Buddy could “kick your ass sideways,” and Rush was up for the challenge.

Buddy called the tune — Guitar Slim’s “The Things That I Used to Do.” Telling Buddy to start off, Rush said he would follow, but the headliner stood aside, never flashing his own impressive chops, as Buddy played “with the spirit of Guitar Slim [in] my soul — not just the spirit, but the showmanship … and after I played the opening notes I watched myself move to the edge of the stage and jump into the crowd, just as I’d seen Slim do.” The crowd went crazy. The owner of the club called Muddy Waters and told him to get over fast, there was someone he had to hear.

After Buddy was done, the club owner told him, “The Mud wants you.” Buddy’s “frazzled mind” misunderstood him to say, “Someone wants to mug you.” Once that confusion was straightened out, Buddy was talking with, and being fed salami sandwiches by, one of his musical heroes while the two sat in a red Chevy wagon parked outside the 708 Club.

Buddy confessed that “tonight was the night I almost called my daddy for a ticket home.”

Muddy replied, “Tonight you found a new home.”

This is where a writer may be tempted to say, “and the rest is history.” But there were many more obstacles to overcome before Buddy’s prodigious talents as guitarist and singer were widely recognized. His first recordings went nowhere after the owner of Cobra Records was found floating in Lake Michigan after possibly having run afoul of the mob. When Buddy finally recorded under his own name for Chess in the early ‘60s, he made a batch of recordings that were, to be honest, artistic successes but business flops that went mostly unheard until years later. For a long time, Buddy was “driving the tow truck, fixing flat tires, and changing batteries” while earning chump change playing session guitar to support his family and his music.

In 1964, on one of those mostly ignored Chess recordings, Buddy sang “It’s your time right now, woman / but I got a feelin’, it’s gonna be my time after a while.” Eventually it was his time, chiefly because the music that went almost unnoticed here, was given serious attention in England where Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck listened studiously to the guitarist who not so long before was listening studiously to his blues heroes. One time, during a lull in Buddy’s recording career, Clapton told him, “I’ve copied all your old licks. How am I going learn your new licks if you don’t have a new record?” In 1986, Clapton proclaimed that Buddy was “without a doubt the best guitar player alive.” In 2005, after Buddy had recorded a string of superb records, Clapton and B.B. King were the inductors for Guy’s enshrinement into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

I asked my friend Peter Parcek — a superb guitarist who proudly confesses his share of copping Buddy’s licks — to describe what he hears as unique in Buddy’s music: “There’s a velocity in his playing. I don’t mean he plays a lot of notes, but there’s a quickness, a pressure to move. He fires off these bursts of notes, phrased surprisingly, starting sooner than you think, or ending before you expect. He toys with the beat, toys with the bar lines, but he never breaks time. And his bends! … he overbends his strings, much more than a half-step or a whole-step. It’s almost as if he bends them right off the fretboard. But it’s quick. He doesn’t hold the bend ’til it sours, just to the point where it cries … His playing always surprises me. His solos aren’t scale-driven, or arpeggio-driven. They’re driven by what he feels. I don’t know where he’s going until he gets there. And until he brings it home, it seems to teeter on the edge of failure. But he doesn’t fall.”

When Muddy Waters was dying, he gave Buddy Guy an order: “Motherf_ker, don’t let these blues die.” And in this seemingly unending farewell tour that lands for one night at Hancher, Buddy’s just following Muddy’s order, doing all he can to provide life support for the music created to succor the downtrodden and downhearted.

Blues is a kind of musical alchemy transmuting sorrow into dance. Or as Buddy puts it, “Funny thing about the blues: you play ’em cause you got ’em. But when you play ’em, you lose ’em. If you hear ’em — if you let the music get into your soul — you also lose ’em. The blues chase the blues away.” Tonight, there will be a whole lotta chasin’ goin’ on.

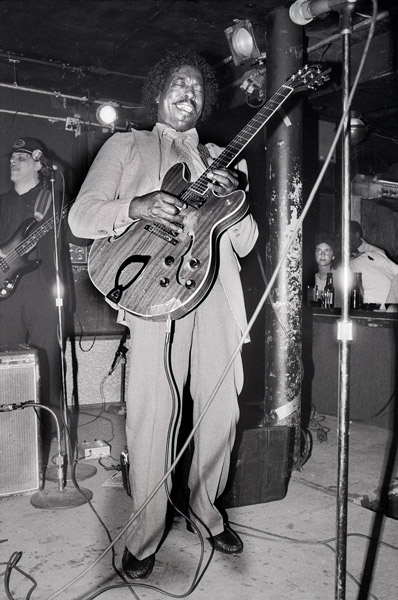

Buddy Guy driving to a gig; Cambridge, MA; c. 1980

Photographs by David Herwaldt